Crypto Scam Risk Calculator

Enter Investment Details

Scam Warning Signs

Scam Risk Assessment

Risk Level:

Based on article statistics, myanmar crypto scams have caused $10 billion in losses with 66% year-over-year increase.

Estimated potential loss: $0

- Stop all communication immediately

- Report to FBI's IC3 at ic3.gov

- Contact your cryptocurrency exchange to freeze funds

- Keep all transaction records

In 2024 American victims lost almost Myanmar crypto scams $10billion to a web of fraudsters based around the border town of Shwe Kokko. That figure represents a 66% jump from the previous year and has turned Myanmar into a notorious hub for crypto‑investment con games, romance swindles and forced‑labor camps. The U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) finally hit back in September 2025, sanctioning dozens of individuals and companies while exposing a hybrid criminal‑military ecosystem that thrives under the protection of armed groups.

Scale of the fraud in numbers

According to the FBI’s 2024 cyber‑crime report, cryptocurrency‑related fraud accounted for $15billion in global losses, with U.S. victims alone shouldering $9.9billion. Southeast Asia supplied the lion’s share, and Myanmar’s operations were responsible for two‑thirds of that American loss. The year‑over‑year increase was driven by three factors:

- More sophisticated social‑engineering tactics that blend romance narratives with high‑yield investment promises.

- Easy access to low‑cost mobile data and messaging apps that let scammers reach thousands of potential victims per day.

- Weak local regulation and the de‑facto immunity granted by armed ethnic groups.

How the networks pull off the scams

At the heart of the operation is a classic "friend‑first, money‑later" playbook. Victims are contacted on platforms like WhatsApp, Telegram or Instagram where a seemingly genuine relationship is cultivated for weeks. Once trust is earned, the scammer spins a story about an exclusive cryptocurrency fund promising 30‑50% monthly returns. The victim is then asked to transfer crypto to a wallet controlled by the network.

Technical sophistication is evident. The scammers use:

- Custom landing pages that mimic legitimate exchanges.

- Automated chat bots that handle routine queries while human operatives manage high‑value negotiations.

- Mixers and privacy‑oriented blockchains to obfuscate the flow of stolen funds.

Because crypto transactions are irreversible, victims often discover the fraud only after the funds have been laundered through a chain of wallets spread across multiple jurisdictions.

Geography and protection: Shwe Kokko and the Karen National Army

Most of the scam compounds sit in Shwe Kokko, a remote free‑trade zone near the Thai border. The area is effectively a lawless enclave where the Karen National Army (KNA) exerts de‑facto control. The KNA, designated by the U.S. as a transnational criminal organization, provides security, taxes the operations and suppresses any local dissent.

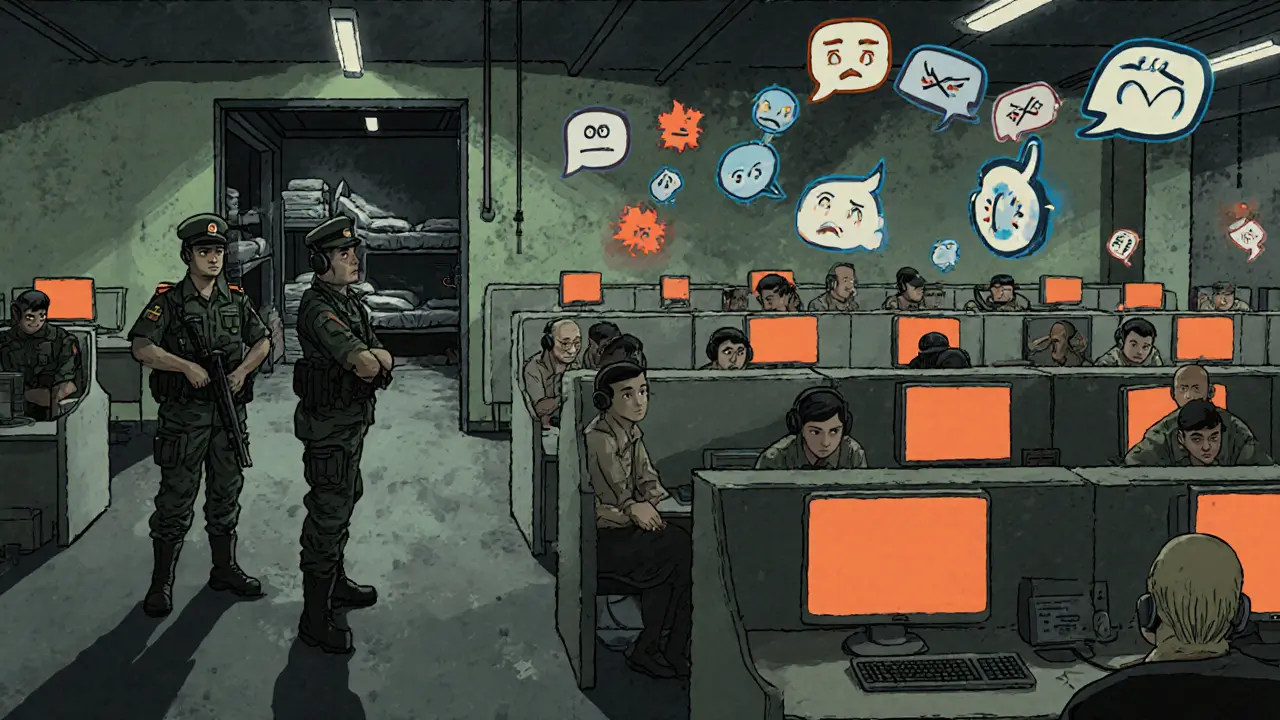

That protection allows the fraudsters to run massive call‑center style facilities staffed by hundreds of workers who are themselves trapped in modern slavery. The combination of geographic isolation, armed oversight and proximity to Thailand’s financial infrastructure makes Shwe Kokko an optimal launchpad for global crypto scams.

Who got sanctioned? Key individuals and companies

OFAC’s September92025 order named 19 people and entities across Myanmar and Cambodia. The nine primary Myanmar targets include:

- Tin Win - alleged mastermind behind multiple investment schemes.

- Saw Min Min Oo - senior operative overseeing the romance‑scam division.

Corporate structures sanctioned:

- Chit Linn Myaing Co. - registered for “mining & industry,” actually runs the primary crypto‑wallet hub.

- Chit Linn Myaing Toyota Co. - provides fake vehicle‑investment fronts.

- Chit Linn Myaing Mining & Industry Co. - same owners, different legal veneer.

- Shwe Myint Thaung Yinn Industry and Manufacturing Co. - supplies the physical infrastructure for scam‑centers.

- She Zhijang - foreign financier linked to capital flows.

- Yatai International Holdings Group - a cross‑border holding company used to move crypto proceeds.

- Myanmar Yatai International Holding Group Co. - Cambodian affiliate supporting the same network.

Human‑rights abuse: modern slavery inside the scam compounds

While the financial numbers stun, the human cost is equally harrowing. Workers are recruited abroad with promises of white‑collar jobs in customer service or tech. On arrival, they discover cramped dormitories, no legitimate contracts, and debts inflated to impossible levels. The KNA enforces compliance through:

- Physical beatings and threats of execution.

- Debt‑bondage contracts that tie workers to the compound indefinitely.

- Coercion into forced prostitution as punishment for “non‑performance.”

These practices qualified the sanctions under Executive Order13818, targeting human‑rights abusers, and have forced the U.S. to treat the operation as both a financial crime and a trafficking case.

U.S. government response: sanctions, executive orders, and inter‑agency coordination

The Treasury’s action leaned on a suite of executive authorities:

- E.O.13851 - targeting transnational criminal organizations.

- E.O.13694 - addressing malicious cyber activity.

- E.O.13818 - punishing human‑rights violations.

- E.O.14014 - focusing on threats to Burma’s stability.

Under Secretary John K. Hurley highlighted the “dual nature” of the threat: financial loss for Americans and modern slavery for thousands of workers. The State Department, led by Secretary Marco Rubio, pushed for broader diplomatic pressure on neighboring Thailand to clamp down on money‑laundering pipelines.

The enforcement effort also involved the FBI’s cyber‑crime unit, FinCEN’s proposed rulemaking to flag Cambodia‑based money‑laundering risks, and the Independent Community Bankers of America lobbying for tighter reporting requirements on crypto transactions.

Comparing Myanmar’s scam model with other regional operations

| Region | Primary Scam Type | Estimated U.S. Losses (2024) | Protection Mechanism | Human‑Rights Abuse? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myanmar (Shwe Kokko) | Romance + Investment fraud | $9.9B | Armed ethnic group (KNA) & free‑trade zone | Yes - debt‑bondage & forced labor |

| Cambodia (Phnom Penh hub) | Investment scams, fake ICOs | $1.2B | Corrupt local officials | Limited evidence |

| West Africa (Nigeria, Ghana) | Romance scams (non‑crypto) | $0.7B | Weak law enforcement | No systematic labor abuse |

| North Korea | Crypto‑mining ransomware | $0.4B | State‑run cyber army | State‑controlled labor, but not trafficked workers |

The table makes clear why Myanmar’s operations stand out: they blend the highest financial losses with a militarized protection layer and widespread human‑rights violations.

Implementation challenges and what lies ahead

Even with the sanctions, dismantling the networks will be tough. The compounds are hidden in dense jungle, the KNA can move assets quickly, and crypto’s pseudonymous nature lets the scammers switch wallets in minutes. Analysts warn that without regional cooperation-especially with Thailand’s financial regulators-new front‑ends will pop up in neighboring towns.

Future enforcement may focus on three fronts:

- Targeting the financial “on‑ramps” that convert crypto into fiat, using AML‑CFT (anti‑money‑laundering and counter‑financing of terror) frameworks.

- Coordinated diplomatic pressure on the KNA, possibly linking sanctions to a cease‑fire agreement in the broader Burma conflict.

- Enhanced victim‑recovery programs that trace blockchain transactions, freeze wallets and repatriate funds where possible.

Industry projections suggest that if these steps are taken, the growth rate of Myanmar‑based crypto fraud could slow from the current 66% annual increase to a more manageable 15‑20% pace.

Key takeaways for readers

- Myanmar’s crypto scam ecosystem extracted nearly $10billion from Americans in 2024, far outpacing any other single region.

- The scams blend romance‑building, high‑yield crypto promises, and sophisticated money‑laundering tricks.

- Shwe Kokko’s location under KNA protection creates a hybrid criminal‑military enterprise that also enslaves its own workers.

- September2025 OFAC sanctions targeted 19 individuals and companies, marking the first major U.S. move against these networks.

- Effective long‑term mitigation will need regional cooperation, AML enforcement, and continued blockchain‑tracking innovation.

Frequently Asked Questions

How did the U.S. Treasury identify the Myanmar operators?

Investigators combined blockchain analytics, undercover online work, and tips from victims to map wallet flows back to companies registered in Shwe Kokko. The FBI’s cyber‑crime unit then linked those wallets to known front‑companies, enabling OFAC to name the entities in the sanction order.

What should a victim do if they’ve been scammed?

First, file a report with the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3). Then, contact your crypto exchange to see if the wallet can be frozen. Lastly, keep all communications and transaction IDs for law‑enforcement follow‑up.

Are the sanctions effective in freezing the scammers’ funds?

Sanctions immediately block U.S. persons and entities from dealing with the listed targets, and many global banks have complied. However, because the funds often move through offshore mixers, additional coordination with foreign regulators is needed to fully stem the flow.

Do other countries face similar crypto‑scam problems?

Yes. Cambodia, Nigeria and even Russia host sizable crypto‑fraud operations, but Myanmar’s blend of high‑value loss, armed protection and forced labor makes it uniquely dangerous.

Can the KNA be pressured to stop supporting these scams?

International pressure, including targeted sanctions on KNA leadership and linking aid to human‑rights compliance, is viewed as the most viable route, though it depends on broader Burma peace talks.

Comments

Reading through the whole saga feels like watching a high‑stakes thriller where the villains wear business suits and the battlefield is a digital wallet. The layers of crypto‑tech, romance ploys, and armed militia protection make this a perfect storm for exploitation. What's shocking is how the sanctions finally pierced that veil, yet the underlying human‑rights abuses persist. Hopefully this shines a light on the need for coordinated regional AML action.

Absurdly corrupt.

This article exposses a deplorable confluence of financial crime and forced labor. The author occasionally mispell words, but the message is clear.

The scale of loss is mind‑boggling, and it underlines why community education matters. If more people knew the red‑flag patterns, the entry point could be closed earlier. We should keep sharing resources like this.

Wow-another billion lost to crypto crooks!!! Who even trusts these schemes???!!!

Really, another one of those “too good to be true” pitches?

Just another night‑mare for the gullible.

I feel for the workers trapped in those compounds; it's a horrific abuse of power. Their stories deserve more attention than just a footnote in a sanctions list. We must amplify their voices.

This is heartbreaking! The victims are not just numbers; they're families whose lives have been ripped apart. We need stronger safety nets and faster reporting tools. Stay vigilant, folks.

Sounds like another circus act with crypto clowns.

The forensic blockchain analysis cited here shows how meticulous investigators have become. By mapping wallet flows, they can pinpoint the front‑companies and apply sanctions effectively. Still, the challenge remains to freeze assets before they’re mixed away.

Wow, this is eye‑opening! 🌟 Let’s keep spreading the word.

The intertwining of organized crime, state‑level sanctions, and crypto anonymity creates a perfect storm that is uniquely terrifying. Victims are lured in by the promise of astronomical returns, a tactic that preys on both greed and desperation. Once trust is established, the scammers demand crypto payments, exploiting the irreversible nature of blockchain transactions. The involvement of the Karen National Army adds a layer of militarized protection that most criminal enterprises lack, effectively turning the region into a safe haven for fraud. Workers inside the compounds are forced into debt‑bondage, with the threat of violence ensuring compliance and silence. This modern form of slavery is exacerbated by the lack of legal oversight in Shwe Kokko, a free‑trade zone that operates outside the reach of conventional law enforcement. The U.S. Treasury’s sanctions on 19 individuals and entities mark a significant step, but the effectiveness hinges on international cooperation, especially with Thailand’s financial regulators. The sanctions block U.S. persons from dealing with the listed targets, yet the funds often traverse offshore mixers, evading immediate capture. Blockchain analytics have become a pivotal tool, allowing investigators to trace funds across multiple wallets and jurisdictions. However, the sheer speed at which scammers can switch addresses poses a constant cat‑and‑mouse game. Regional diplomatic pressure on the KNA could potentially weaken the protective shield, but it must be balanced with broader peace negotiations in Burma. Meanwhile, victims are left with limited recourse, underscoring the need for robust victim‑recovery programs that can freeze wallets and repatriate assets. The rapid expansion of these networks suggests that without sustained pressure, new front‑ends will emerge in neighboring towns. The article’s data underscores a 66% year‑over‑year increase, a trajectory that can only be curtailed through coordinated AML frameworks. Ultimately, this crisis illustrates how technology, when weaponized by organized crime, can amplify human suffering on a global scale.

Cool read, thanks for sharing.

Great breakdown-keep the insights coming! :)